It is always a pleasure to share interests with another; fellow hobbyists can attest to that. In this case, familiarity does not breed contempt. However, to share both hobbies and disciplines can be a bonus.

I met Wilson Low through the Triathlon Family Singapore website, and its gatherings of members at local races. We also raced at Ironman Malaysia 2008, and we subsequently completed the Ironman 70.3 World Championships together in Clearwater, Florida in 2008. Wilson crossed the line at about 4:39:18, and that established him as one of the fastest Singaporeans for the 70.3 Ironman format. A month before that, he qualified and completed the Ironman triathlon in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii in 10:54:25 – 14 minutes improvement over his first attempt at the Ironman triathlon in Western Australia in 2006.

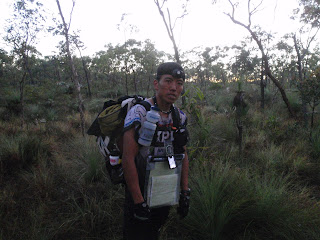

Wilson’s approach to training is scientific, and it belies his approach to coaching triathletes and adventure racers. He trained in Spartan style, at times twice daily when he was training for triathlons. His personal approach may appear brutal, yet that brutality translates into race-day conditions that the trained body must and will endure. It takes discipline to stick to a plan, deny oneself from pleasant distractions, calm down during a race, and even to back off from one’s ego. It is a thin line between being utterly focused to being self-possessed or obsessive.

Endurance sports and writing are, in themselves, disciplines. Wilson is actively involved in online product reviews. He has a broad knowledge about sports equipment, training and races. Having done the Big Three in endurance sports, he is now focused on adventure racing and professional coaching.

Conducting this interview was a journalist’s dream, for I did not have to edit much; he has a major in journalism from university. I have left Wilson’s words verbatim, so that you get a strong sense of his personality, energy, and drives.

Enrico Varella: How did you get involved in endurance sports?

Wilson Low: In 2000, I spent my first three months of junior college in the Outdoor Activities Club for my Co-Curricular Activity. A friend I knew through the club suggested I check out the Eco-Challenge Borneo that was going on at that time. I saw the coverage of this epic multi-day, non-stop, expedition race on the Internet – including a Singaporean team completing against tremendous odds and a very demanding course - and decided from that day on that I had to do a race like that in future.

EV: What is your background in sports? Which sports or events did you participate in?

WL: Later on in junior college, I was on the school kayaking team. During that time, I did running to keep fit, and bought a mountain bike in my senior year. I promptly fractured my hand falling off that bike a week after finishing my A-Levels, waited six months for it to recover, before enlisting for National Service. During that time, I kept up running and started adventure racing more frequently.

EV: Which is your favourite format in racing: Olympic Distance, 70.3, Ironman or Adventure Racing?

WL: Without a doubt, AR. I am first of all an adventure racer, and only dabbled in triathlon just to keep fit! Of course, I have enjoyed some success at the various triathlon distances as well, but it’s the constantly varying nature of AR that continues to appeal to me. No two AR events are the same. Typically for a given event, the formats, sequences, distances, and course profiles are always changed year on year.

EV: How important was coaching to you?

WL: Being coached taught me the principles of training within one’s means and to avoid the ‘trial and error’ course of action that the majority of recreational athletes take when deciding to pursue a sport they are passionate about. The idea of being coached is really just the idea of getting an objective view on an athlete’s training progression: by acknowledging weaknesses, avoiding pitfalls, and maximizing the quality of the (limited) training time that athletes have.

EV: What and who inspired you to assume coaching as one of your professions?

WL: I sincerely believe that in Singapore, there is a shortfall of quality coaching, particularly for off-road specific disciplines; and that few coaches, if any, bother to address the mental and tactical aspects of endurance racing. For the latter point, it is my opinion that the best mindset for endurance sports participation (and from there, developing strategies and tactics for athletic success) is something that can be nurtured, and is not necessarily innate. For the former point, living in Australia taught me the differences between sporting cultures in Western and Asian societies, but also that the disparity between them is closing fast as Asian affluence rises. For that reason, skills instruction that is easily imparted in the military (navigation) or overseas (amidst technically demanding water bodies, and mountainous trails) has to be tweaked and delivered within a local, civilian frame of reference. The more Singaporeans challenge themselves with endurance races, the more they will seek to go overseas to test their limits – and that’s where being adept at both the soft and hard skills of the sport really come into play.

EV: As a graduate, where you could qualify for an indoor profession why did you decide to brave the great outdoors?

WL: Being indoors would have killed me. University life reinforced the idea in me that being desk-bound for money, and being half-hearted about it, could never be as fulfilling as being paid to do something you truly love, and can do well. My experiences doing sport and being in the outdoors convinced me that it is possible to challenge convention and build a career out of it, even in outdoors-scarce Singapore. It is my conviction that this line of work will be mine for the long run, and as a result, I take my work very seriously and expect nothing less than top quality service for my clients.

WL: It has to be my first win, where my kayaking team (most of us being under 18 years of age) won the relay race for the first-ever Singapore Adventure Quest AR. Just for a laugh, we had named our team after our kayaking coach, who was also on the team. We were just thankful that there was a lot of kayaking in that race. Another one would have to be crossing the finish line of XPD 2006 on my birthday after more than seven days on the go. It was my first expedition AR, and there was a birthday cake, champagne, and pizza waiting for our team at the finish line.

EV: Between Ironman triathlons and adventure racing, which is your preference? Why?

WL: I love both kinds of events, for different reasons. Ironman is primarily a solo endeavor, so all the mistakes are your own – but so is the glory! Solo events that require self-discipline and self-motivation for long periods of time without interaction with anyone else are the best form of ‘me’ time that an endurance athlete can have. However, the inter-personal dynamic of most AR events (being team events) is what I find myself more attracted to. I often find a sort of dynamic leadership scenario develop during particularly arduous AR events. The strongest team member may not be the strongest one all of the time; it may fall upon the team member who is in the background to take a stand and assume a leadership role in certain situations when the strongest member of the team is down, for instance. On a related note, sometimes a different perspective coming from a ‘supporting player’ in the team dynamic can create solutions when there seems to be no other way in the ‘lead players’ eyes.

EV: How is adventure racing different from triathlons?

WL: True adventure racing has no set distances, sequence of disciplines, or a marked and marshaled route – self-navigation becomes an essential skill. Sometimes, race organizations only let racers know part of the course and release the remainder only along the way after the race has started. You also have the potential to accumulate much more equipment (toys) than the average triathlete. AR is a gear freak’s dream sport. Many athletes enjoy the predictable and homogeneous format of triathlon events in that course distances are set to a standard, and its descriptions/profiles known well in advance. AR calls for an athlete who embraces a hardier, ‘can-do’ spirit - in the same vein as that of early pioneers or explorers. That being said, a triathlete makes the best kind of athlete to cross over to AR. The mentality of maximizing efficiency – pace control, not stalling during transitions, doing everything on the move - is something that is commonly seen in triathlon, even amongst the rookie athletes. This is not the case in AR, with the exception of the most experienced and elite teams, who seem to have gotten maximizing efficiency down to an art form.

(To be continued tomorrow…)

Photo-credit: Wilson Low